Dan and Morgan continue their now totally off script discussion about sci-fi’s roots in colonialism. Watch out! There’s some pretty stark racism being quoted in this one so, if that’s hard for you to hear, maybe come back next week! Otherwise, strap in. Also, the James Webb telescope hasn’t launched yet! It’s scheduled to join with the expanse on Dec. 25th.

Listen to “Ep. 6: Colonialism, Part 2 [CONTENT!]” where you get Podcasts.

Recommended Reading:

Tunnel in the Sky by Robert Heinlein

Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction by John Rieder

Footnotes:

Transcript

[Ad]

[Music fades out and voices fade in]

Morgan:…And that kind of deals with the human effect of like people that are Colonized. So instead of just about like how we address natives, it’s like how do we actually deal with being the Colonizer. Yeah.

Dan: I mean—

M: This is not great.

D: No.

M: It’s not like, just rich white people conquer the world, sometimes it’s like desperate, hungry people that have to like, go make a new way like how they do in The Expanse when they go through the Ring-gate.

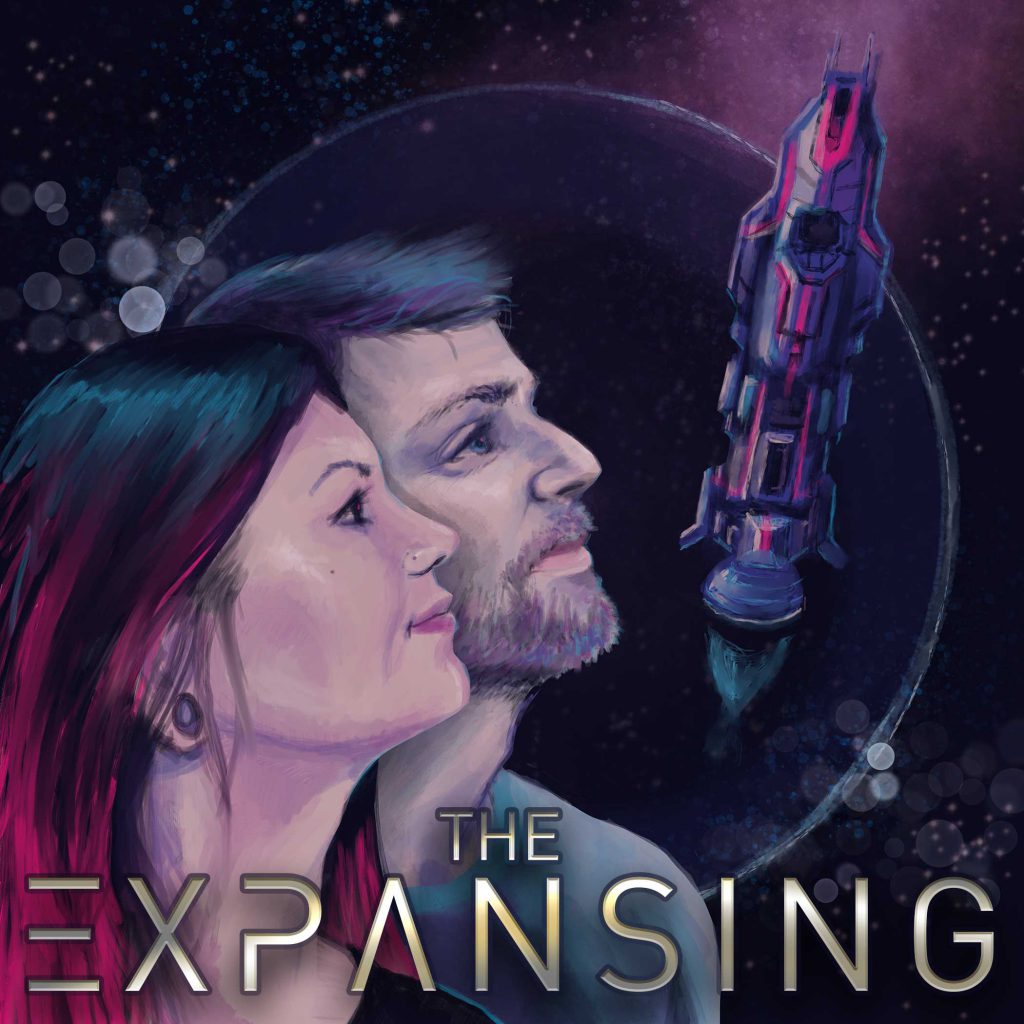

D: Right, right, right. But that, on that show that we’re supposed to take about: The Expansing wait, no, that’s our show. The Expanse is what we talk about on The Expansing, which you’re currently listening to for some reason. Uh, My name is Dan Winburn and I am joined today by a mononym. Or…

M: I’ve actually shortened it to just Mo.

D: Mo? Okay.

M: Yeah.

D: My co-host Mo. And we’re going to talk more today, this Part 2 about Colonialism in SciFi. [Part 1 here] And we didn’t talk about The Expanse that much last time. But obviously a lot of the story and the universe, as we see it in The Expanse, is representative of something that we would we would label as Colonialism like, there’s these pockets of people out in the asteroid belt that are basically not in full control of their lives because other, you know, companies and such own their stuff or their the rights to the places they call home. But also because when the Ring-gates open, we suddenly have all these these new worlds to explore, all of which are supposedly at this point in the story uninhabited. Right?

M: Ooh.

D: But what does that even mean, really? The more I have thought about that and the idea of, of our rights to do certain things, this is really representative of that same kind of white person colonial mentality of the actual “Age of Exploration” where it’s like, “Well, you’re not using it, so I’m going to use it.” And it’s never implied that there’s not life on those planets.

M: Yeah.

D: In fact, they encounter that life, and some of it tries to harm them.

M: Yeah.

D: And yeah, because that’s, that’s it’s planet. You’re the invader, you’re the invading alien.

M: With flora and fauna.

D: Whether or not you’re intelligent is irrelevant to that general fact, right? You’re invading this planet and you’re spreading your own, your own microcosms everywhere and trying to, you’re going to have to, they’re going to have to deal with that. And things might not go well, but also, how do you know that you’re not in the presence of some kind of consciousness? How do you know that they are not sentient beings on this world? Maybe they, maybe they have a completely different structure?

M: Yeah. And every footstep that you leave on the surfaces is permanently altering the ecosystem.

D: Right.

M: There was an old SciFi short story about, you know, these two guys that were basically exploring uninhabited worlds and they would pop down to take some samples, take some photos and then they break for lunch.

D: Hmm.

M: They wrap up their garbage and supposedly, you know, seal it, sealed containers and bury them in the sand. And they’re like, All right, let’s get off this planet and onto the next one. And whatever life form existed on that planet was contaminated by their lunch refuse and it destroyed all the life on this planet just because they set foot and like, left their sandwich wrapper.

D: Right.

M: So like, what right do you have to the water in the air versus like the dragonfly that evolved to actually live there? [laughs]

D: Right. The idea that again, to think about like a sentience, there are lots of SciFi stories and maybe like there’s also some stuff in Star Trek and, and there’s some, some literary examples that I’m forgetting because like, there’s this one thing I’m thinking of an I can’t remember what it is from, but it’s like these beings that don’t seem to be anything. But then they come together in like kind of a cloud formation, and during that time, they develop.

M: Hmm.

D: They are intelligent beings during that time, like they become like a mind.

M: Yeah. Yeah, that—

D: And then they break apart again, and they perceive humans as being these weird collection things that, that don’t have minds of their own. And they try to figure out humans. And it’s like, What if there’s something like that out there, we don’t know! We don’t know.

M: Yeah.

D: It’s an alien planet. We’ve never been on one. What do you, why are you assuming that you can just come in here and take it?

M: Well, that’s like in the Stranger in a Strange Land where they get to Mars and the Martians are just like floating blimps that they think are just like nothing. But they’re actually extremely intelligent, telepathic. And that’s where the term “grok” comes from, which was like, really popular in the seventies.

D: Mmhmm.

M: But it’s to understand something so completely that you understand it at an atomic level and you can, like, unmake it physically. But to us, they just look like little floating hippos.

D: [laughs] There’s been a lot of things like that, though, where something is so alien to us that we just didn’t even realize it was thinking.

M: Yeah.

D: And that is not really acknowledged at all in The Expanse, but it is, it is a weak point as far as like the morals of the culture or of the society that it’s representing. Because, as you said, that the settlers are are desperate—

M: Mmhmm.

D: —and you’ve got to, you got to be pretty desperate to go down to an alien planet and be like, we’ll be OK. But that notwithstanding, the efforts of the scientists and the crew there to extricate them and to make sure they don’t get any of the stuff is so far over the top. This sort of evil colonialist attitude?

M: Yeah.

D: That I’d feel like they really wanted to hammer that home.

M: Right.

D: Because there are 1000 habitable planets we just found, and you’re bitching about this one, you could have just gone through a different gate.

M: Yeah.

D: Like. They went through first. I guess it’s theirs now. What rights do you have to say that isn’t theirs?

M: Well—

D: What court are you standing in to say those planets that somebody found? Those belong to me. [snickers] Those belong to this government. Like, uh, says who?

M: Well, this very, very week—

D: It’s wild logic.

M: The islands of Barbados just secured its independence from the—

D: That’s true.

M: —fucking Queen of England. And why does England have Barbados?

D: Right.

M: Right. What are they getting out of it?

D: Because they took it.

M: Yeah exactly.

D: Because they with military technology—

M: Yeah.

D: —that was advanced beyond what the people there had. That meant that they were able to kill them better. And that is kind of a weird macrocosm of, of how a lot of times evolution will work. And that lets, that sort of misunderstanding of what evolution is led a lot of people to think, well, it’s OK because we’re better than them.

M: Right.

D: So…

M: You’re “Manifesting your Destiny.”

D: Right.

M: Yeah.

D: And that’s very much the Manifest Destiny thing comes up for sure in The Expanse. But in the 19th century, especially, a lot of these formative stories that we were talking about last time, were basing that assumption on the colonialistic experience of encountering these quote unquote “primitive cultures”—

M: Right.

D: —and saying, “Well, we’ve evolved beyond them. So that means we’re, we’re the fittest so we can do. We can do what we want to them.”

M: Yeah, they’re assuming that “civilization” is a straight line and that if we have a sufficiently advanced technology that anyone who doesn’t have it is actually behind us on the scale?

D: Right.

M: Which means that they are less developed or less evolved when really the only real factor is that their life has not necessitated the advancement of that technology. Right? If you live, if you live on an island, why would you ever conceive of a car?

D: Right.

M: No, like, you would just be fishing?

D: The only real reason that, that most people participated in the colonialist, I don’t want to say experiment because we’re living through a few centuries of it. This this gigantic expansion of Western control. It wasn’t because people were exploring because they were curious.

M: No.

D: It wasn’t because they were like, “Oh, neat, we can go places.” And they knew places existed before they just figured out that there were more of them than they thought before, right? They found, for them, they found a new place that they didn’t know existed before, but those people knew it existed and they were hanging out and doing their thing. Right? And all of that was driven by the need for money—

M: Yeah.

D: —because they, they said, “Well, if we go there, we can find gold and we can go up and take it. It’s going to be lying there and we can get something for nothing.”

M: Well, there’s really two drivers for emigrating or colonizing. One is money, obviously, to go get resources because to pay somebody else, to ship it to you. This is why we we wanted spices so bad.

D: Mmhmm.

M: Because there were merchants that would go along the merchant routes to get the spices.

D: Absolutely.

M: And so by the time they came home, the trip had been so expensive that the cost of those spices were high. Obviously, duh.

D: Right.

M: This is like Trade 101. So there were plenty of capitalists that were like, “Well, we just seize the means of production.” [Dan laughs] Like, we find a faster way there. We own it and we it’s just ours. There—

D: Yeah. But it’s very logical.

M: Yeah, I mean, that’s how we have billionaires. The other side of that is just running out.

D: Mm-Hmm.

M: You know, Western Civilization ran out of space and food and water.

D: Yeah.

M: And actually, in the last century, there was a crisis. There was a food, global food crisis where it was getting to the point where the soil that we were planting crops in just couldn’t replenish nutrients fast enough. We were very, very concerned about what we were going to do, and this is why we invented—

D: Looking your way, Interstellar.

M: Yeah, this is why we invented fertilizer, because it was like, “Holy fuck, what are we going to do? We can’t get nitrogen into the soil. Naturally, we have to solve this.” And this was 100 years ago, not even.

M: Yeah. So that’s a lot of what drove people to colonize other parts of the world.

D: And it’s this, to talk about evolution, what is happening. It’s not that a particular people are better or worse or any of that thing morally, but if you want to talk about culture driving any kind of evolution, the culture of the country or the land that goes and takes things like this from someone else, that’s especially from a place that is so different, it inevitably and inexorably changes them. And that is sometimes good because it can add more ideas to their philosophy, but it also corrupts them because they become an unwilling part of this system that now includes those things, which means that you are going to feel that that’s what life is like. And so you’re entitled to that if you live in. A place where that’s available, right, and it’s the same sort of thing we have in this country with wealth disparity, it’s like, “Oh, well, I deserved that because everybody else has that like my, my my friend down the street has has a pepper mill. He puts pepper on his on his food. It’s it’s great. It’s amazing. I need to have that. I should have that.” Right? Which means that you justify whatever actions need to happen to get that stuff. And that creates that demand, which means that people can make more money,—

M: Yeah.

D: —which means they’re willing to go out and do anything to get that, to get more of it, right? And then that just begins to diversify and to intensify and becomes not just pepper, becomes, oh, this this particular type of of cloth.

M: Cars.

D: This, you know this, this car, that particular material, this phone, you know, and now it’s it’s that system that we, so many of us live under where we expect these modern things, these modern conveniences, but we don’t actually technically need them. We need them culturally, because we do things culturally, that like and I mean as a as a as a living being, we don’t need them like, we need them to function in the system. But, you know—

M: Yeah, to exist in society.

D: —because there’s there’s modern humans existing right now on, on a subsistence sort of level that, that are perfectly happy because they don’t do any of the modern stuff, quote unquote “modern stuff” that we do, which is really just technological stuff.

M: Yeah, but I don’t know if it’s fair to say that we don’t need this stuff because like, I drive an SUV. I’m not super proud of that. [Dan laughs] My tradeoff is that I don’t use paper towels, but I have to have an SUV to do the work that I do. It’s not a status thing about—

D: Right. Oh. No, no, I meant on a really, for you to survive physically, you do not need most of the things that we have—

M: No, but…

D: —because there are people in the world that don’t have those things.

M: But we live in a society where you don’t have the option to not live without this.

D: Oh yeah, No. I’m acknowledging that. I’m just saying that because of that, we’ve, all of us everywhere in the world—

M: Yeah.

D: —have become like that where we feel that drive to. We need that thing. A lot of that started with the commodities and the resources that we just sucked out of the rest of the world into Europe.

M: Sure.

D: The money, the spices, the actual like, people, sometimes.

M: Yeah.

D: The, the physical goods, all of that stuff just poured in and started creating this economy that could develop all this stuff. And it’s, it’s like a virus. It’s or it’s more like a cancer I think.

M: I think it’s more like, it wasn’t necessarily like greed or jealousy or a sense of entitlement to the same success that your neighbor had. I think at some point what happened was people that had the means to explore the world or put up a little bit of capital and buy a whole factory, you know, so now they own the means of production, which means their profits increase and they can live this lavish lifestyle. I think other people saw that and thought it was easy because this is somebody from maybe the same neighborhood or the same, you know, country of origin, but they were able to achieve all this. “So why can’t I?” But this is the thing. There’s no consequence to that kind of dominion.

D: Right.

M: So if we go back 1000 years, if you and I like, wanted to move somewhere new, we would have to do a lot of hard work and maybe die in the process—

D: Oh yeah.

M: —and use the labor of our bodies to cut down trees to make wood, to build house, to hunt for food, to set up stables and lose some of our livestock.

D: Right.

M: And it would be grueling work. And at the end of that, we would have something that we owned, but we would have had to work so hard. And once you have something like money or capital that comes into play, that’s imaginary. Money is not real. [Dan laughs] But like, I have some gold coins that I can use to spend on this, you this stuff—

D: Right.

M: —and then I just acquire this sort of like, it’s a fiction, and it made it easier for people, I think, to covet that kind of lifestyle. I don’t think it was about wanting the thing per se. I think it was about wanting to work less for more.

D: Oh yeah. No. It’s what I’m talking about is a little bit more of an umbrella than what you’re saying. And what I’m meaning is that that the the spoils of, let’s just call it, “Empire” because colonialism and imperialism its own kind of blurs together.

M: That’s all it is.

D: The spoils of empire that benefit the the emperor or whoever is at the top in, in the worst kind of way. Trickle down economics is not real as we understand it, but that society then benefiting from those things that have been drained from elsewhere corrupts, the society—

M: Because it becomes necessary. Yeah.

D: —in a really fundamental way, because now all of the people in that society view all of those things as now necessary to their lives.

M: Yeah. I see what you’re saying.

D: I think the people who are making them and not giving them to them are now the bad guys somehow, even though they’re saying, “Well, hey, stop killing us.” [laughs]

M: Yeah.

D: Like they they become part of the system and they support it. I mean, it’s very Matrix in that sense where you’re supporting it while also viewing yourself as separate from it. Because “No, no, no, it’s rich people that do this. I don’t do that. I just need my spices.”

M: Well, in a way, aren’t we stuck here, though, because like—

D: I don’t know. [laughs]

M: —if we it did want to go, let’s say we did want to go live off the land. What land? All of the lands belongs to somebody, you know, we couldn’t just go out into the woods or go into the Yukon. It’s like, where are you going to go to, like, set up your little sovereignty to yourselves and be left alone?

D: Right.

M: You can’t. Everything belongs to somebody and you can’t access any of that shit for yourself. Unless you like—

D: Speaking of belonging to something else, we have to interrupt our conversation for the corporate overlords so that we can advertise for things.

M: Yes, all hail the corporate overlords.

D: Hail!

[Ads]

D: Speaking of space, so in The Expanse, we see the sort of result of that, right? That there’s no room left on Earth.

M: Right.

D: Holden’s family is one of the lucky ones, and they had to jump through a bunch of hoops to make that happen.

M: Well, even before that, it was Mars.

D: Oh yeah.

M: Mars was a colony.

D: Right. And so we got people on Mars, people on Earth. It’s getting crowded and then people move out into the Belt and then they’re still getting harassed by the people from quote-unquote “Back Home.” Right? It’s like even if you do that thing and the people that make the run through the Ring.

M: Yeah.

D: Even if you go for a place where you can be away from everyone at a certain point, someone’s going to come you.

M: Yep.

D: They’re constantly probing. But you’re right. There’s there’s nowhere to go.

M: Because we have two kinds of colonialism. Yeah, you have the Capitalists and then you have the desperate people.

D: And Dune is is a really good example of the kind of very specific Age of Exploration type of colonialism like very, you know, Pirates of the Caribbean in most people’s mind.

M: Mmhmm.

D: And in terms of that, that sort of era like what we talk about, the ships on the high seas going vast distances to collect—

M: Something, maybe.

D: —collect commodities, people, chattel.

M: Hopefully.

D: Yeah. And make a bunch of money and bring it back. And in Dune, Arrakis, is it, you don’t get this in the movies, but it used to be a better place. It sort of became that way. And it’s being drained constantly of the one thing that makes it a special place still in terms of resources, which is the spice.

M: Mmm.

D: I mean, it’s pretty on the on the head. Right?

M: Yeah, that’s.

D: Herbert just calls it the spice. [laughs]

M: It’s a pretty hammer to forehead allegory.

D: It’s really a story about that kind of struggle where it’s like whether you want to think of it as oil or think of it as spices. It’s these people who just want to be, have, they’re sort of sitting on something that they don’t think of as valuable in the way that the colonialist power or the imperial power thinks of it as value.

M: Like Aztec gold.

D: The value to them is different.

M: Yeah.

D: And they don’t want it gone. They just wanted to stay there, to be there. It’s this perception that goes through a lot of these early stories, especially and in a lot of colonial thinking, “Well, this is something that needs to be exploited and they’re not doing it. So I’m allowed to. I’m allowed to go take it from them because they don’t know how to use it. They’re just dumb. They’re primitive. They don’t have the smarts that I do with my big, my big brain. And so I can go, take that stuff and be mean to them because I will be in fact helping them by bringing culture to them.”

M: And religion.

D: Mmhmm.

M: Yeah.

D: That also reminds me of the the kind of pretty heady racism that imbues a lot of the early SciFi stuff because it does piggyback off those sort of adventure tales where you have these quote unquote “savages” that don’t know better or even something like The Time Machine.

M: Yeah.

D: You know where there’s there’s this obvious bad guy type of things that are slightly different, right? But some of the early stories were much more, much more aggressive in their presentation of this and much more un-self-aware, I guess. So this is quoting from Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction. Quote: “in Frank Aubrey’s 1897 The Devil Tree of El Dorado, the first humans the protagonists encounter in El Dorado, or our white girl and a darker skinned man pursuing her. The explorers shoot the man, thereby incurring both the lasting gratitude of Luma, the girl who turns out to be a princess.”

M: Oh my God.

D: “And the enmity of the vicious high priest whose son they have slain.” [Morgan scoffs] The guy chasing the girl. Anyway, continuing: “The pattern of saving the princess from a vicious enemy and simultaneously establishing, establishing the explorer’s superiority through the use of deadly force recurs in Robert Ames Bennett’s 1981 Thyra, a Romance of the Polar Pit, a novel that employs a number of the devices that Burroughs later used most successfully.

D: Yeah.

M: So, this is from the Thyra that was just mentioned. Quote: “‘I heard a sound of running footsteps. Imagine my surprise when a girl, a white girl, [Morgan scoffs] came into view running at top speed, not 50 yards behind her came a group of men or beasts for I couldn’t tell at first glance which they were.’ Our hero leaps to the rescue. ‘With a shout, I stepped from my hiding place and threw my rifle to my shoulder. I had four shells in my rifle and four of the blacks went down. I could work the bolt.’”

M: Oh my god! [laughs]

D: We should we should probably add a trigger warning in here. [Morgan continues with a sharp inhale] “By the time the scene is done, he has killed 14. In all three cases, the key point is that the explorers establish an alliance with a good native who looks and thinks the way they do against local enemies, and they do so by shooting the enemies with a gun.”

M: Oh my God.

D: Yeah. And there’s there really is so much of that, and it’s usually presented in much more, in a less horribly racist fashion. But there’s that huge element in a lot of SciFi where the all of the conflicts that are the big ones that people remember are just, just violence. It’s the really interesting stories that involve a lot of like more cerebral story beats fall through the cracks.

M: Yeah.

D: Like a lot of the big things, it’s like you go shoot the problem. That’s what you do. That’s what’s cool.

M: Yeah.

D: That’s what’s fun to watch. And I mean, so like the book Starship Troopers, being so different from the movie is a good example of this—

M: Right.

D: —massive divide between these two halves of the SciFi realm. Right? Bullets versus brains in terms of—

M: Yeah.

D: —how do you talk about these stories? What’s important about these stories?

M: Yeah, because the book Starship Troopers, the goal is diplomacy. It’s just acknowledging the fact that we only have one way to get there, which is through force.

D: Mmm.

M: Whereas the movie was just like a gore fest like, yeah, that is very interesting. It’s always through some like, display of power.

D: Mmhmm.

M: It is a weird power fantasy. The Explorer, the—

D: Yeah. And that’s another thing about the—

M: —Adventurer.

D: —social consequences like the societal cultural consequences of like just the average person on the street knowing that these grand adventures happened in real life, like the these guys that have the company, they went on that ship and they went over there and they had an adventure, right? And they did these amazing things and they came back and they got rich and they hear about that.

M: Mmhmm.

D: And it’s a real thing that really happened to those individual people. And it starts to become this thing that you sort of fantasize on your own.

M: Yeah.

D: Even though you’re a regular person, it starts to become a thing you, not really aspire to, exactly, but, but daydream about or think would be fun, and it becomes part of your cultural upbringing where you know that these things happen and people go.

M: Which is how you end up with people that will like, buy cell phones in bulk and resell them. And, you know, because that’s that’s the same mentality is like, you go dominate the ivory trade and you get rich, you know, like or whatever the case is.

D: Well, that plants a lot of seeds, though, as well in, in people’s minds, the minds of readers. And then when you start to get to the the Industrial Revolution, that’s when we see as we were talking about some of the early books before we, were there, there’s this sudden turn from literature were there’s more of a fantastical nature like Mary Shelley is usually regarded as at least part of early SciFi.

M: Yeah.

D: I mean, she was writing very early with Frankenstein and—

M: Yeah.

D: —SciFi, as we know it, it’s really more like about 50 years later. But once you have the Industrial Revolution and people realizing that, and the Scientific Revolution of understanding the motions of the planets and acknowledging that they’re there and being able to see them with better telescopes and have these machines that can take us places so fast and it suddenly becomes much easier to believe that you could do it, that you could really go, that it’s real, that this is not a fantasy and you’re no longer interested in reading fantasy novels because you think, “No, no, no science has unlocked the realms for us.“

M: Yes.

D: “We don’t need your fantasy anymore. I want to read about something that I believe could happen to me.”

M: Right, which is—

D: “Because I want to go on an adventure and the world is already full.” Because colonialism already sucked it dry.

M: Which is why Science Fiction is usually regarded as something that could be true.

D: Yeah, exactly. When we were talking about sort of defining the genre before.

M: Yeah.

D: That’s, that’s one of those things that I think is necessary when you talk about it, it’s like, Well, we got to understand that the idea of SciFi as we think of it just didn’t exist until some of the things became possible, like Jules Verne talking about going to the Moon. I mean, that was before rockets were a thing.

M: Or a submarine.

D: We had things that could do stuff that was very powerful that human beings could barely imagine before. So it was like, “Well, that doesn’t seem so fantastic anymore.”

M: Yeah.

D: “That doesn’t seem like sacrilege. It doesn’t seem like the suicidal thoughts of a maniac.” You know. It’s…

M: So, Edgar Allan Poe actually wrote some early Science Fiction too, which a lot of people don’t know, but one of my favorite short story—and this was, I mean, he was just getting published, you know, at the time for a paycheck. But he wrote this short story. I think it was just called like A Voyage to the Moon. So simple, but it was an extremely detailed account of a man who basically built a hot air balloon to take him to the Moon. And it’s like his journal of, of his journey along the way. And he describes like altitude and the air density and how he gets to the Moon and the basket actually like flips over to to land on the moon. And there’s little inhabitants like waving at him.

D: I mean, that’s but it spot on with what you’d have to do with the balloon.

M: It was such a clinical ex—like detailed account of a voyage to the Moon that it was believable enough that people actually thought it was legitimate scientific journaling.

D: Right.

M: Which is so crazy. Let’s— and it’s the same thing happened with War of the Worlds.

D: Yeah, I was I was going to say this is like around the same time that a lot of these stories are happening. Like, like you were saying, the future history type things where like, there’s something called A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder from 1888.

M: Hmm.

D: You’ve got War of the Worlds from 1898.

M: Yeah. And the thing about War of the Worlds is it’s almost insulting to believe the narrative that’s out there that, like people heard a radio drama and just lost their minds and rioted and killed themselves. That is not what happened. [Dan laughs] It started a minute or two before this previous show that was really popular at the time had ended. So a lot of people missed the intro that said “And now, a radio drama.”

D: Right.

M: And it opens with a news broadcast that’s part of the radio drama. And if you listen to the rest of it, it’s like it. It is what it is. It’s a radio drama. As people like, you know, actors conversing, but the beginning of it is this news broadcast which sounds legit. So what actually happened is people heard the first part of it. They thought it was real. Five people got really upset about it. That was it. It wasn’t mass panic.

D: But the reason that it even got any of that traction is, when the book was written, we were already at the point of colonialism being such an important part of just reality. It was the system to the point where we were getting books that were essentially satirizing the concept by turning it on its head and saying, “Well, what if they did that to us?”

M: Yes.

D: And that was in 1898.

M: Yes, and which is where visitors come from, invaders…

D: Like decades later. People hear that and they are still like, that’s become part of our sort of—

M: Fear.

D: —background hiss of our lives, of knowing that, “Well, the things I have are better than the things some other people have and people like might want to come and—“

M: Take it.

D: “—do bad things to us. Like, what if that happened? I wouldn’t want that to happen.” But also, of course, all the paranoia and things that are surrounding most of the 20th century. But that concept of of “Oh, no, what if it happened to us?”

M: Yeah.

D: —also drives this sort of weird defense mechanism that happens like in The Expanse. I found it interesting when the scientists who they murder is talking about—

M: As you do.

D: —an enemy who already fired the first shot because they see what the Protomolecule does to things.

M: Right.

D: Right? And so they perceive that as evil. It’s bad. It’s against them. It must be some sort of enemy instead of just it being, that’s what it does, and it doesn’t know.

M: Right.

D: But that notwithstanding, they kind of leave out the idea. They’re like, “Well, what? What are they going to do to us because we know what we went through to them.”

M: Exactly.

D: But that molecule has been there since before humanity existed. It was sent there by beings who are doing exactly who were doing exactly the same thing that the humans in The Expanse are now doing with the Ring-gates by going onto this planet where nothing conscious or sentient exists and setting up shop. That’s what they were doing.

M: Mmhmm.

D: And if you think of that as an enemy firing the first shot. Then what are you? Right?

M: Yeah.

D: You’re doing the same thing. You’re bringing your form of life to another alien world that doesn’t have, like a living civilization on it right now.

M: It’s just can’t fight back.

D: And taking over.

M: Yeah, even if it did have life forms, if it was like, boars.

D: Oh yeah, it wouldn’t matter.

M: Or deer, it wouldn’t matter, it wouldn’t stop us.

D: I mean that’s why—

M: But should it though?

D: —we have these stories about invading aliens. Is we, number one, we do it to each other anyway.

M: Yeah.

D: And we would totally be the ones doing that to other species if we had better technology than we would do it.

M: Is it really that bad, though?

D: Well. We get another example of getting it done to us later on in the story, which you are not privy to because you haven’t read the books. But spoilers ahead. As in right now, long after the events of the series, we encounter the Martians who factioned off and left and ran off.

M: Oh yeah.

D: And we find out what they’ve been up to for approximately 30 years. In the meantime, and what they’ve been up to, is developing lots of bad US military technology using the Protomolecule because they got that other scientist when they captured him.

M: Yes!

D: And so they come back through the Ring-gate with a giant warship that is like nothing they’ve ever seen and Drummer’s there and like a few other like characters we remember, I think it was Drummer, but I have to go back and check and they’re all just like, “Oh my God, what is this?” And they just. And they send some stuff out it and it just atomizes some ship, right? Just got this crazy weapon all of a sudden.

M: Oh my God.

D: They’re basically coming back to start their new empire. And well, yeah, that’s what would happen too, if people had the chance, right? And there. And yeah, it’s another kind of turning it on its head, which I don’t think The Expanse does any better than most things at avoiding the pitfalls of having been raised in this world, like in terms of just storylines, like you’re always going to have a little bit of are you defending this or you not like, there’s going to be weaknesses here and there, but it’s interesting to me that they managed to have several different takes.

M: Yeah.

D: And the idea of the Martians suddenly coming back a few decades later, and now they are. “We’re in charge now.”

M: Well, is that?

D: Doing that to the entire rest of the species. [laughs]

M: But I know this is going to be incredibly unpopular, but like, is it so bad? I mean, like us going through the, OK, so as going through the Ring-gates and like colonizing of distant planet that might have flora/fauna, even some kinds of ordered life. Is it a bad thing that we do that?

D: Who says it’s good? Who says it’s bad? If you’re talking about alien world, it’s like, Well. That’s sort of something human society has to decide at that point. Right.

M: Yeah.

D: It’s a matter of what is what isn’t. Because if you were talking about, well, the problem with that, though, is that you have things that are on a spectrum. And I know some people hate that word, but it’s just truth. So when we’re talking about sentience, when we’re talking about what lives are worth something, there’s a little bit of a spectrum there, too, I, is my opinion, because if you’re talking about a mosquito, I’m will swat a mosquito without thinking. Right?

M: Right.

D: And I don’t think that that makes me a bad person, but it probably does the mosquito. But I’m not going to just walk up and stab a dog. What level of sentience are you fine with stepping all over?

M: Right.

D: How, where do you draw the line? What, what beings?

M: But even, even—

D: Because some of those animals are animals, especially in the books, you get a lot more descriptions of different types of fauna.

M: Yeah, but even if there were animals there that were just like dogs. So what are we supposed to just leave that planet alone—

D: Well, Yeah.

M: —because maybe in 1,000,000,000 years they develop—

D: That’s the question.

M: —into a higher order and they can travel this? Or do we just fucking settle it? Like, there are too many people…

D: I mean it drives it into—

M: We gotta…

D: —the question of how much of this is human nature—

M: Yeah.

D: —and how much of it is our systems that we’ve created forced us to be this way. Because, we’ve—

M: I don’t think we are.

D: —gone on for hundreds of thousands of years as a species, but we only just started like big making buildings and guns and stuff. It’s very, very new.

M: Yeah. Arthur C Clarke said that we’re the first age to really think about the future.

D: [laughs] Right.

M: We might not have one.

D: Right. [laughs]

M: We’re like a little too late to actually having foresight to we’re like, Oh shit, now that we can conceive of the future of mankind. Uh, might, might have missed our shot. But I mean isn’t survival now?

D: Yeah, I’ve had that sort of existential despair ever since that Star Trek episode “Inner Light.” M: Yeah.

D: Which in the view of this conversation is a weird sort of reversal of that in the sense that Picard has this entire world and and memories and culture forced into his brain without his consent.

M: Yeah.

D: And it changes him. Changes and permanently as an entity, as a person. It was it wrong of them to do that to him if it helps preserve their entire society. And now so many others will learn about it at these sorts of rights and wrongs become very muddy when you talking about different cultures, different species interacting with each other because we do vicious, terrible things to so many species.

M: Right now.

D: We’re monsters, like actual storybook monsters to most things that live.

M: Yeah, if people knew what kind of, what the landscape in North America looked like.

D: Oh, I know.

M: Where we just brutalized it. It would blow your mind. There were buffalo everywhere. The Rocky Mountain, there was like a beetle that like it would just black out the sky.

D: Yeah, I was going to say that the idea of the scale of flocks.

M: Like, the amount of the Rocky Mountain locusts would block out sky and devastate crops and made it… But you know what? We just destroyed their habitat, and now they’re extinct. So fuck you. Passenger pigeons dead. Like all like it used to be so different, and we’ve already just obliterated it all.

D: Mmhmm.

M: We look at the endangered species list now and nobody gives a shit.

D: Mmhmm.

M: You know what I mean about saving the last panda? You know, like.

D: Well, we’ll just clone them later.

M: I—[laughing] yeah.

D: I think some people the, the problem is…

M: Stick it in an environment it can’t live in.

D: Something that that not enough people are grappling with, I think, is that we’ve gotten so far along technologically that we’re actually there at the point where a lot of people are going to start losing their grip on actual reality—

M: Yeah.

D: —because they go to the movies and see something amazing and it’s like, No, we can’t do that. No, we can’t.

M: Or got to a zoo…

D: That’s, it’s make-believe. [laughs]

M: Yeah. Or like, you watch Tiger King and you see somebody had like 300 tigers seized and you’re like, “Well, the tigers are everywhere. They’re fine.” They’re not everywhere.

D: Well, we’ve also got like actual dinosaurs zoos you can go to now, with like moving around dinosaur robots and stuff.

M: Yeah. They’re actually not in the wild, which is where they should be.

D: It’s not real. [laughs]

M: That’s the issue, is like…You know…

D: Make robot tigers, is the message.

M: We should.

D: Honestly, we should. We should fake any animal products.

M: Actually…

D: We should fake if we can do it with technology, including things like leather, including things like actual tigers, so that we can leave the ones in the wild, alone and stop killing them.

M: That was actually that was a subplot in a in a Heinlein novel that rich people actually, it becomes fashionable to have designer pets. And so they bring all these creatures back—

D: Oh, they’ll definitely do that.

M: Yeah. From the brink of extinction.

D: I would take one. Wouldn’t you want to design your pet.

M: Or like a tiger? That’s the size of a cat?

D: Yeah. That’s in Jurassic Park, too.

M: Yeah.

D: They talked about that as like one of the other things the company does terribly.

M: Or like a little great white shark. It’s only only like 18 inches long.

D: Yeah.

M: So you can keep it in the tank. I would do that in a heart. In the middle of this sentence, I would put a down payment—

D: Ok.

M: —on a cat sized tiger.

[Ads]

D: Ah, but The Expanse, the one last thing I want to talk about as far as like how what life is and like, do we have a right to mess with this and the very idea of the protein molecule?

M: Right.

D: Right. They immediately think, how can we exploit this?

M: Yeah.

D: Not what is it? Are we curious about? I mean, they do learn about it, and certainly some of the scientists are massively curious, although they’ve been they’ve had their parts of their brain removed. But it’s but it’s like, OK, so when this thing gets big enough, whatever you want to call it, that, that sort of networked system of whatever the protein molecule really is, it starts to do things and communicate with other parts of itself. Kind of like a like a network.

M: Right.

D: Like it’s communicating like things that have minds do.

M: Like a Neural Net?

D: So is this conscious?

M: Yeah.

D: What are we doing here? Like, there’s no… they immediately just: “How can we exploit it? How can we turn into a weapon?” And that’s also pretty believable.

M: Yeah.

D: As far as the colonial sort of mentality of like, I need this to help me somehow, well, how can I use it? What can I do with it?

M: Yeah, how can I use this to…

D: Instead of just: “Oh, isn’t that amazing that that exists?”

M: Yeah.

D: Isn’t that neat?

M: How can I use it before someone uses it against me?

D: Right? This is sort of very adversarial thinking, but Jeff Bezos? Mentioned recently…

M: What did Daddy Bezos do?

D: Yeah. He mentioned recently that because of his nice little trip to space, you know, he’s got all this perspective now. He thinks that, you know, we’re going to need to have everybody live and work in space so that the Earth can remain like a, kind of like a park where only some people will live.

M: The poor people.

D: Uh, No, I think he means the opposite.

M: Oh, fuck! So like, Earth’s going to be Fiddler’s Green.

D: Yeah.

M: Uuuuuuuuggggghhhhh!

D: They’re like, Oh no, you’ll work up in the factory open space and you’ll have these huge ships that will have gravity. And you’ll just like, we will have so many room for so many more people and then we can depopulate most of the Earth and make it nice again.

M: Oh my God.

D: For all of the rich people to live on.

M: I guess that explains why, like four of my friends deleted their Amazon Prime accounts today.

D: Yeah, I was like, “Oh man.”

M: Holy shit.

D: “What are you doing, bro?”

M: Somebody just.

D: Like, you’re turning into an actual villain.

M: He is.

D: The mega yachts that, hey, we should probably, we should probably send, all the poor people into space.

M: I think we have bigger issues with humanity than just like one crazy guy with $1 billion.

D: Yeah.

M: $400 billion.

D: He’s got a few billion.

M: Yeah. It’s not even real money. So well, that’s fucking that’s bleak if that idea catches on.

D: Yeah.

M: And the fact that he thought about it means that other people are going to think about it.

D: But here’s the mindfuck. It’s bleak.

M: If you’re a rich guy, that is your solution.

D: Well, yeah, but it’s bleak, but it also makes me think. What if he’s right?

M: Yeah.

D: Because what’s better, if you had to choose? The Earth dies and maybe humanity struggles on in these like horrible pods or underwater things, or habitable underground stuff, right? Or the thing Jeff said.

M: Yeah.

D: Uuuuuuuuuuggggghhhhhh…

M: I mean, my my plan and my, [Dan laughs] you know, my dream for the future is free birth control. You know, like I think that just population planning would probably help.

D: Yeah. No.

M: Um. Maybe not like a one child policy, but like there’s a lot of steps we could… But here’s the thing how do you convince people that the planet is dying and it is our fault and we have to save it because it might fail us when they literally believe that they’re going to be raptured off of it?

D: Yeah, and that’s another aspect that I meant to talk about. We’ll just have to mostly skip over, which is right. [laughs] But the justifications, yeah, for continuing to do the colonialist stuff that we recognized was bad, like hurting people, taking their stuff, taking their land, that sort of thing. Well, they’re savages, right? They don’t know about Jesus, and we got to save them.

M: Yeah.

D: So now what we’re doing is good. In fact.

M: Right.

D: It’s been this really super good justification. Like great. Glad to have it, said all of the early capitalists. Yes, yes, we do.

M: Yeah, we…

D: We also need to bring the Bible with us. Absolutely.

M: We’ll go and build schools, but they’re going to be Mormon and we’re going to give all the kids Bibles. Yeah.

D: Right. And I liked the Mormons did show up in The Expanse. That was a nice touch.

M: It makes perfect sense.

D: It’s a nice touch.

M: Yeah.

D: All right. I think we’re going to have to wrap up. I mean, that’s, we touched on things. There’s so much more. I mean.

M: There there is a Heinlein book. I don’t know if you want to talk about it real quick and try to wedge it in there, but it’s called Tunnel in the Sky, and it’s about basically Earth is overpopulated. They develop teleportation, so it’s very much like the Ring-gate.

D: Mmhmm.

M: And they teleport little colonies of people to other planets, and it’s basically about a group of essentially teenagers that are teleported through space time to an uninhabited planet and their teleporter breaks. And they’re isolated for a couple of years, and they have to set up their own government, which is something Heinlein is obsessed with is government.

D: Oh cool. Yeah.

M: And how people resolve that problem of society. So…

D: Yeah. And I wish more authors were—

M: I know.

D: —because it’s like, that’s what our problems are.

M: I know, it’s very like…

D: Everything about like, modern life that’s hard—

M: Is society…

D: —is people getting other people to listen?

M: Yes. So it’s very like the Moon is a Harsh Mistress where it deals so much with like, how do we govern ourselves? But it’s also basically like these. You know, they’ve had to revert back to primitive technology because they’ve lost their connection to all of these modern resources.

D: Mmhmm.

M: And then, you know, the teleport is fixed and they bring them back home and they treat them like fucking children, [Dan laughs] you know, and they’ve just done like years in space—

D: Right.

M: —basically inventing civilization and staying alive. And then they come home and things are so different. It’s like a massive culture shock.

D: Right.

M: And it was it’s so interesting how that connects with The Expanse, you know, because it is very much like sending humans to the Belts or to Mars and how it creates this distance and how forcing people…

D: It’s much easier to be terrible to people that are you never see.

M: Yeah. And then having to figure out how to survive in harsh conditions with limited resources and then treating them like they’re idiots or like they’re incapable of taking care of themselves? Yeah. So Tunnel in the Sky.

D: I like kids that don’t get stranded.

M: Yeah. [laughs] I like kids that have working teleporters.

D: There are a lot of good teleporter stories out there, actually.

M: Yeah. So Tunnel in the Sky is uh, and it’s a story about colonizing, but like being the ones who are colonizing out of necessity.

D: Mmhmm.

M: You know, it’s not about like taking over native people and obliterating a natural landscape. It’s about just like we will. We do. Have we had to do it at one point, gonna have to do it again? We have to because Mars is dead. If we had access to an Earth like planet that had oceans and trees, we would go and I don’t think you would care what was living there.

D: Yeah.

M: So.

D: I wanted to end on a more fun note and say, let’s do a game of…

M: Fuck, Marry Kill?

D: Yeah, I was just I was going to say “Bang, Marry, Kill.” But from specifically, uh, I guess The Expanse.

M: Ok.

D: Let’s, let’s turn it back and try to refocus right here at the end when we’re talking about, you know, silly things.

M: Yeah, let’s get off the heavy stuff. Who do you want to fuck? [both laugh]

D: So tell me.

M: Uh, so do I have to give you 3? 3 choices and then you choose?

D: Right? That’s… no.

M: OK.

D: Oh yeah, yeah. Yeah, you give me the three.

M: Yeah, OK. So so. Uh. ooh. Camina Drummer. Ashford. [laughs] And. Oh, shit. Nancy Gao.

D: Oh. And that’s easy.

M: Yeah?

D: Yeah. Uh, I think I’d fuck Drummer.

M: OK.

D: And I’m, a little caveat here because you have to read the book. So marry Ashford. Because he’s a sweetie.

M: OK.

D: And and kill Nancy Gao because she sucks.

M: Yes, she does suck.

D: Also, I bet Drummer is dynamite in the sack.

M: Oh yeah. Isn’t that all the more reason to marry her?

D: Yeah, but, you’re going to have, you got to have that resonance with the personality? I think. I think he and I get along better.

M: I see that.

D: Also the little singsong stuff he does now and then it’s…

M: Yeah, I was going to say he’s musical.

D: In the books he’s way more of a jackass, like he sucks in the books.

M: Yeah. I think, I think you guys would hit it off.

D: All right.

M: Nancy Gao, it was a given.

D: Yeah. Obviously. I think you just…

M: She’s a little hottie with a body.

D: I was going to say, I think you just wanted to see which one I would kill.

M: Yeah. [both laugh]

D: Uh, OK, Miller.

M: Shit.

D: Uh, Avasarala.

M: Uhhuh.

D: Fred Johnson.

M: Fred Johnson! Oh, god damn it. Oh.

D: I went in a different angle. Kidnapping the characters I think you like.

M: Yeah, he’s so cool. Okay. Well. I couldn’t see myself coming home to Miller every day.

D: Hmmm.

M: I feel like he’s the kind of guy who’s married to his job.

D: It seems like it.

M: Do I get to personally kill them?

D: Sure.

M: I get to kill them. OK. OK, I’ll fuck Miller. I’ll marry Fred Johnson.

D: Hmm.

M: And I’m going to choke Avasarala to death while we bang. [Dan laughs] Ok?

D: All right fine.

M: Did I find that loophole?

D: As long as she dies.

M: That’s part of it. It’s an autoerotic execution.

D: You think she’d be into it?

M: Uh, Yeah. I think we’d have a lot of meaningful eye contact and her beautiful brown eyes glaze over. She’d touch my cheek.

D: She’s really just like Cheryl from Archer.

M: [laughs] Yes. She likes pain.

D: So I think we’re going to have to wrap it up. My name is Dan Winburn. You can find me on Twitter if you want to. For some reason @DanWinburn, D A N W I N B U R N. And you can also follow us, and you should definitely follow us @TheExpansing on Twitter. We do fun little retweets and do jokes and things, but it’s fun. It’s fine. Go look at it and the stuff. Morgan, can people find you on the internet?

M: Yeah, you can find my erotic…

D: I’m sorry, “Mo.”

M: Mo. I guess I can shorten it every episode. Next week, I’m just going to be a gesture. Yeah, you can find my artwork and my erotic fiction about The Expanse on Instagram @LuxNovaStudio or on Facebook.

D: Maybe you should actually write some FanFiction and then we can put that on, on…

M: On a Patreon? [both laugh] Or like really? Really Rule 34 Fan Art.

D: Yeah. Yeah.

M: I would do it for enough money. I mean if the price is right.

D: OK, bye.

M: Bye. It looks like you froze. Your face froze and I was like…

[music fades in and the voices fade out]

[Ad]